You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Culture’ tag.

My husband and I have been married for just over two years now. One of the things that we really like to do together is go for walks. We walk through our tree-lined neighborhood, holding hands, and chat about our days, the weather, all of that average, mundane stuff that relationships are made of. I treasure those walks.

While we are walking, we rarely get a second glance. A neighbor or two might glance up and smile in greeting or extend an “ ‘Evening” but rarely do we get much more than that. I’m okay with that. We aren’t out for a walk to be recognized or announce anything about ourselves to anyone else. We are simply strolling at dusk, anonymous and happy.

While we are walking, we are anonymous. We are just a couple, like any other.

Another couple might be walking at the same time we are walking. They, too, might have been together for over five years and be highly committed. They may presently struggle with many of the same things young couples struggle with: defining their couplehood, maintaining family of origin relationships and navigating emergent adulthood. They, too, may someday plan on buying a house, planting a garden and raising children.

When this couple walks, though, they are not anonymous. They may be gay or lesbian, biracial, or have any the other characteristics that seem to require explanation. In short, they deviate from “the norm.”

Over the past year, this has really struck me. When I’m thinking about what being oppressed and privileged means, I think that one of the primary clues that I’m thinking about a category of privilege is that it does not require explanation. When my husband and I walk at dusk, I feel like I can rest assured that nothing is assumed about us. We could be liberal or conservative, parents or childless, in touch with our families or not.

As far as I know, holding my husband’s hand is not regularly construed as an overt political statement.

One of my assumptions is that all people have been both recipients of privilege and victims of oppression. Where in your life are you oppressed? Where in your life are you privileged? If you are having trouble defining these areas, think about the parts of your life and context that demand explanation. What does that mean?

*Many thanks to Dr. Terri Karis and Dr. Bruce Kuehl, two professors at the University of Wisconsin-Stout, who got these ideas rolling.

A recent study put out by Emory University looked at brain development for adolescents who engaged in risky behaviors. In spite of previously assumed theories issuing that risky behaviors were associated with the underdeveloped adolescent brain, researchers found that from a structural standpoint, adolescents who engaged in risky behaviors actually showed more highly developed white matter. Researchers suppose that this may be due to the increasing complexity of performing adult like behaviors and the extended adolescence American culture employs throughout the college years. Erik Erikson believed the primary conflict of adolescence was Identity vs. Role Confusion. As opposed to 100 years ago, when adolescents were expected to be married and raising families by their 20th birthday, 20 year olds are typically college sophmores, just deciding a major and generally figuring out what it is that they want to do with their lives. That task of sophmore year, and the college years in general, fits in well with Erikson’s postulate on adolescence. Because of extended adolescence, teens’ brains may mature before they have the wisdom and life experience to make healthy decisions or engage in safer risk taking (as opposed to anti-social or delinquent behaviors).

Hennepin County Medical Center is developing a rooftop garden to grow special herbs used for Hmong womens’ after-birth meal. I think that this is a pretty amazing effort for the hospital and hopefully it Hmong women to feel welcome there.

Pioneer Press (2009, July 11). HCMC entices Hmong mothers with rooftop garden. Retrieved July 11th, 2009 from http://www.twincities.com/news/ci_12816996?source=rss

To begin this post, I should put myself, as its writer, within context. I am a Christian Lutheran. I am white and have really only lived within Modernist American culture. I like science, and although philosophically I identify myself as Postmodern, scientifically, Modernist perspectives ring true for me. When I talk about faith and science, this is the place I speak from.

A recent study put out by the Brandeis University took a look at research studies conducted on the healing power of prayer from 1965 – 2009 and found that the studies actually had very little to say about whether or not prayer played a role in physical healing, but more to say about the role religion played in the researchers lives’ and the overall societal context at the time. For instance, the earliest studies only considered Protestant prayers and only recently have non-Christian intercessions been considered by the scientific community. When conducting the studies, the presence of some basic requirements of scientific experimentation have been lacking, such as true control groups. Brandeis’ study seems to say that extricating something like prayer from its’ web of social, religious, and expectation-based contexts is near impossible. There are some studies that say that prayer is correlated with the person’s health improving, as long as they know that they are the subjects of prayer. Other studies seem to say that being prayed for is actually associated with low rates of positive outcomes. I would venture to say that the effectiveness of prayer has more to do with the belief system of the person who is the subject of prayer and the relationship between the pray-er and the pray-ee. Like many things in science and culture, the larger context needs to be considered.

One of my favorite things about scientific research is how true research isn’t something to be argued about. All research considered fact remains simply not unproven, and if you have a problem with the standing research, go and do a study to disprove it and submit it to the scientific community. One of the things that bothers me to no end is when people say things like they “don’t believe in evolution.” Evolution isn’t a matter of belief. It is a matter of research, and current research most widely supported in the scientific community supports evolution. If you have a problem with it, take a look at the research. Or better yet, examine your own beliefs to see where the dissonance comes from. Is your religious beliefs dependant on research supporting them? From a Christian context, doesn’t Hebrews 11:1 read “For faith is the evidence of things unseen…”? Science, research doesn’t concern itself with things that are unquantifiable. Faith doesn’t need to be proved by the quantified. In the same way, scientific research doesn’t need to fall within ones’ own unquantifiable faith. From the article: “We do not need science to validate our spiritual beliefs, as we would never use faith to validate our scientific data.” Faith and science need not support each other, they stand on their own, with their own supports.

Brandeis University (2009, June 18). The Healing Power Of Prayer?. ScienceDaily. Retrieved June 18, 2009, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2009/06/090617154401.htm

A recent longitudunal study put out by the University of San Fransisco found that family obligation may serve as a protective factor against depression for Chinese American adolescents. A strong family bond may provide adolescents with a secure bond from which to explore the surrounding world while maintaining a home base to return.

This makes me think of the research regarding attachment styles in infants. Infants may have a variety of attachment types which I will explore in later posts, but the goal of attachment is to have a style in which the child feels safe to explore a room, but returns every now and then to “check in” with their parent or caregiver. Maybe adolescents continue to need that sort of “checking in” point to rank their emerging identity against accepted norms within the system. What role do you think family alliance plays in identity development for adolescents?

San Francisco State University (2009, June 4). Family Obligation In Chinese Homes Lowers Teenage Depression Symptoms. ScienceDaily. Retrieved June 6, 2009, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2009/06/090604124804.htm

A popular framework for looking at how families function is on the axis’ of cohesion and flexibility. Cohesion is the measure of emotional closeness. Flexibility is the amount of change that happens in leadership, roles and rules. Both cohesion and flexibility are continuums. The extremes of cohesion are enmeshed and disengaged, whereas the extremes of flexibility are rigid and chaotic. A healthy family typically manages to strike a balance between all extremes. Communication is the grease that allows natural movement. For instance, a family may typically be structured-connected (generally stable roles, emotionally involved) and become enmeshed-connected (generally stable roles, but with little differentiation between individuals or emotionally intrusive) when they experience stress. In contrast, another family may be chaotic-cohesive (little stability in roles, emotionally involved) but become flexible-cohesive (some variation in roles, emotionally involved) when stressed.

A similar framework could be used to look at cultures. How stable are roles within the culture? To what degree is interpersonal or emotional involvement tolerated? The prevailing American culture could be probably easily be described as flexible-disengaged (role change is fairly tolerated, highly individualistic even in familial sub-systems). In contrast, from my understanding of traditional Chinese culture, it could be described as rigid-connected (roles are extremely stable, emotions are shared but not extensively). According to recent research, according this model, positive mood may be the grease that allows individuals to explore cultural paradigms other than their own.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia manipulated participants emotions and then had them take a series of questions exploring their self concept and cultural beliefs. Participants who were smiling or listening to soothing music were more willing to “explore values different than their own.” In contrast, participants who were frowning or listening to music in minor chords more consistently picked values that were their own.

[Researchers] surmise that positive feelings may send a signal that it’s safe to broaden one’s view of the world — and to explore novel notions of one’s self. The researchers go on to indicate that negative feelings may do the opposite: They may send a signal that it’s time to circle the wagons and stick with the “tried and true.” They conclude that the findings also suggest that the “self” may not be as robust and static as we like to believe and that the self may be dynamic, constructed again and again from one’s situation, heritage and mood.

Association for Psychological Science (2009, April 14). How We Feel Linked To Both Our Culture And How We Behave. ScienceDaily. Retrieved April 16, 2009, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2009/04/090414153538.htm

A recent study put out by the University of Birmingham found that ethnic minority students that attend complimentary after-school programs, in which more than one language is used for instruction, report higher levels of self esteem and confidence. For those students, a bilingual identity that stretched beyond the home environment was found to be associated with a more world-wise, modern identity. Additionally, families of students in such programs report greater satisfaction with the education their children were receive.

I thought this study was interesting because one of the factors that was impressed on me most deeply while I was in school regarding immigrant identity, is that there is a shift between the first, second and third generation. The first generation often comes interested in preserving the ways of the country they came from. For instance, they may continue to speak only their first language and learn English only as needed. The second generation are the first children of immigrants born in America. They may serve as the families translators and ambassadors to mainstream American culture. In spite of their role as translators, the expectation may be that they still keep their primary loyalties to their parent’s culture. The third generation is almost entirely American; the culture of their ancestors is sometimes just that, ancestral. The realities of an, at times, jingoistic racism are not lost on the third generation of immigrants. However, their identities are strongly influenced by the American mainstream.

I wonder what effect introducing more complimentary schools with focuses on Hmong and Somali culture would have on gang involvement in the Twin Cities Metro area. With the influx of Somali and Hmong refugees the area has been enriched by in the past few years, Somali and Hmong gang involvement has unfortunately increased. If more complimentary school programs were introduced, would that increase cultural identity and serve the need that seems to be fulfilled currently through involvement with gang affiliation? How would it change or improve first generation immigrants opinions of the American school and social service system? How could social services use complimentary programs to increase utilization among under-served populations? What do you think?

Economic & Social Research Council (2009, February 10). Multilingualism Brings Communities Closer Together. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 14, 2009, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2009/02/090210092721.htm

A recent study put out by the University of Washington found that girls growing up with a parent dealing with heroin dependence, incarceration, mental illness, or violence were four times more resilient than boys growing up in similar circumstances. Resilience was defined as “working or being in school [until adulthood], avoiding substance abuse and staying out of trouble with the law in the past five years.” (Although that may seem like a very minimal expectation, only 30 of the 125 surveyed children demonstrated resilience of that quality.) The sample was taken from children of parents utilizing methadone clinics in Seattle metro areas. The major factor affecting that finding seemed to be that boys more often had criminal charges against them.

I wonder about the affect gender socialization has on that outcome. Are males socialized more to respond in violence to adverse circumstances? Are males actually doing more criminal activity, or are females doing more criminal activity under the supervision of pimps? If males are doing more criminal activity, are they doing it to provide for their families? (If you join a gang, there is an element of protection there, not to mention an opportunity to make some money.) Also, how would the data be different if it were taken from more upper to middle class constituents, or from a third world setting? What do you think?

University of Washington (2009, February 12). Girls Growing Up With Heroin-addicted Parent More Resilient Than Boys. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 13, 2009, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2009/02/090211161859.htm

A study in the Journal of Counseling Psychology looked at differences in help-seeking behavior and etiological beliefs for mental illness and found that when looking that Mainland Chinese, Hong Kong Chinese, Chinese Americans and European Americans, generally, the more Westernized a person was, the more likely they were to seek help for mental illness. They hypothesized that this was due to a difference in the etiological beliefs about mental illness; namely, that collectivist cultures believe that mental illness results from personal factors, like history or life quality and individualistic cultures believe that mental illness results from environmental or hereditary factors. One interesting outcome of this study was that although Mainland Chinese and Hong Kong Chinese were less likely to seek help for mental illness than Chinese Americans or European Americans, Mainland Chinese were more likely that Hong Kong Chinese to seek help. (This is surprising because Hong Kong is considered more Westernized due to colonial history.) An idea that may explain this difference is that in Chinese Universities, school clinics are run by doctors and psychiatrists in tandem; visiting a counselor or therapist is not all that different than visiting a medical doctor.

Some of the questions I have about this study include:

- Does the etiological belief that mental illness results from personal factors lend itself toward more rapid solution focused therapy? (In my own work, I have found that when a client is willing to take ownership for their part in interpersonal conflict, they are able to resolve conflict much quicker. Does it work similarly for larger, more global issues?)

- Would physically integrating mental health and medical care increase utilization for mental health services in general?

- How does one go about determining the etiological beliefs for mental illness in languages that don’t have words comparable to “mental illness”?

Chen, S.X. and Mak, W. W. S. (2008) Seeking Professional Help: Etiology Beliefs About Mental Health Across Cultures. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(4), 442-449

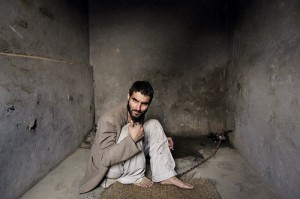

War, cultural beliefs and a lack of infrastructure all have combined in Afghanistan to create a virtual maelstrom for families dealing with mental illness. There is only one hospital in the country with a psychiatric ward, and it has a mere 60 beds, 20 of which are dedicated to treating drug abuse. (A variety of other hospitals in the country have beds for treating people dealing with mental illness, but the focus in those is rarely on treatment.) With the lack of governmental or privatized supports, families who have a member dealing with mental illness often opt instead to bring their mentally ill to shrines around the country where the clients are chained outside when it is hot, inside when it is cold. They are left at these shrines for 40 days and 40 nights and the belief is that God will cure them. In spite of the few improvements that outsiders see, such as lowered blood pressure because of the minimal diet, the people who run the shrines and the families that utilize them report miracles. Individuals are cured regularly the legends report; statistics and observation seem to speak otherwise. In the context of this paradox, 68% of the country is probably dealing with some sort of Axis I disorder.

This article makes me think a lot about the challenges implementing effective medical care of any kind can have within cross-cultural contexts. A year ago or so, I read the book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman, a book about a Hmong family in central California whose daughter had epilepsy. It covers the work the doctors, social services, and family went through to cope with their three year old daughter’s illness. According to the Hmong worldview, epilepsy was a blessing, a sign that she was gifted and was going to eventually become a shaman. According to most of the doctors’ view, epilepsy was an illness that needed treating. According to the social services system view, it was the families right to practice their cultural beliefs however they wanted, as long as they were compliant with her medications. Each system wanted what the best for the child; each system believed that best was something dramatically different. Due to a variety of factors, the child eventually passed away. Throughout the course of the book, the author speaks about individuals in the various systems and one doctor’s appraisal in particular appealed to me. He was the one doctor in the area that the Hmong families most often went to out of choice. When asked why he was so successful with their families, his reply was simple. “Their lives are not my own.”

The lives of the people dealing with mental illness in Afghanistan are not my own. Their plight is not my own. Their problem is not mine, and their solution in all likelihood, cannot come from me. When I first read this article, solutions started to pop into my mind, but am I really even correctly identifying the problem? If the culture in which the people live does not identify a problem, is there one? By the same token, I believe that there are some rights that all people should have access to, regardless of cultural orientation, ethnicity, religious beliefs, or even actual physical availability. In my heart of hearts, I believe myself to be somewhat of an idealist. Medical care is one of the rights that I believe all people should have access to; I believe that mental health coverage is one aspect of that basic right. With that set of biases on the table, I would like to purpose some ideas.

For the situation in Afghanistan, I wonder how effective starting at the ground level would be. Sunni Muslims don’t agree with the use of the shrines talked about in the article, but the article doesn’t cover what the Sunni majority thinks about mental illness in general. I wonder if using Afghani community leaders to educate their own people about mental illness and the effectiveness of treating many of the Axis I disorders the population seems to be dealing with would be effective in curbing the use of the shrines. Perhaps working with the people who run the shrines to develop more humane conditions for the inhabitants would be effective. I would also like to see a systemic study of the effectiveness of the shrines in treating what the families perceive to be the major treatment issues. (If the family’s main issue is violent behavior, how well does 40 days and nights at the shrine effect violent behavior upon return?) Ideally, I would like to see Afghani people doing most of this work as well because I think it would have more credence for the population. What do you think?

American Psychological Association (2008, December 26). Mentally ill suffer in Afghanistan: Afghanistan lacks system to treat them. PsychPort. Retrieved December 29, 2008, from http://www.psycport.com/showArticle.cfm?xmlFile=knightridder_2008_12_26__0000-0231-TB-Mentally-ill-suffer-in-Afghanistan-1226.xml&provider=